Discoloration in the oeuvre of Joachim Beuckelaer

In my last blogpost I have discussed the phenomenon of discoloration in Netherlandish painting (1400 – 1700). I concluded that discoloration is omnipresent in museums. The paintings of the Antwerp painter Joachim Beuckelaer (1533 – c. 1575) are no exception: in his paintings too, discoloration is visible. Beuckelaer is mostly known for his market and kitchen scenes, in which he painted small religious scenes in the background. In art historical literature he is often discussed in the context of the development of the still life genre.

As part of my master’s thesis, I researched three of Beuckelaer’s paintings: The Well-stocked Kitchen (Rijksmuseum), Allegory of Imprudence (Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp) and Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus (Mauritshuis). While I wrote in my last blogpost that discoloration doesn’t affect our appreciation of paintings, I found that the intentions of the artist can get lost because of said discoloration.

One of the first authors to write about Beuckelaer, is Karel van Mander (1548 – 1606). Van Mander was an artist and art critic. He wrote the Schilderboeck (1604), which includes biographies of the most important Netherlandish artists. One of the chapters of this Schilderboeck is about Beuckelaer. Van Mander writes that Beuckelaer was well-trained in painting ‘from life’. He observed nature and imitated what he saw in his paintings. By doing this, Beuckelaer was one of the best artists of his time, according to Van Mander: Beuckelaer was exceptional in his imitation of nature.

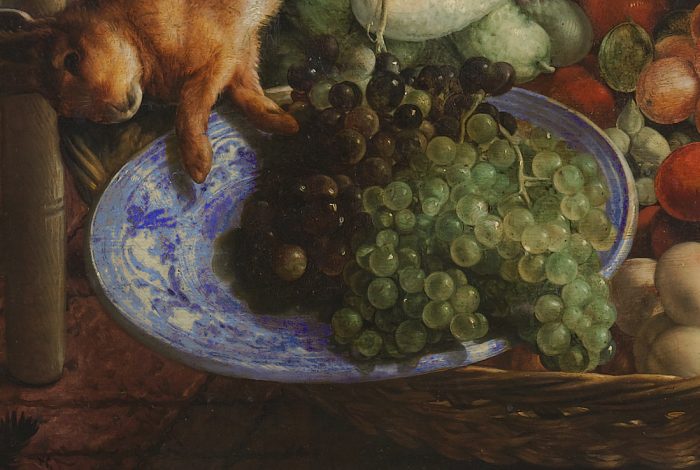

Van Mander also writes about the living conditions of Beuckelaer: the Antwerp painter was apparently very poor and didn’t make much money by selling his paintings. This poverty is reflected in Beuckelaer materials: in a lot of his paintings, the pigment smalt can be found. Smalt is a blue pigment, that was first used in oil painting around 1540. Artists then didn’t know the pigment could discolor, because of a chemical reaction between the pigment and the oil. It will lose its blue color and turn brownish grey. These discolorations can be found throughout Beuckelaer’s paintings. An example is the earthenware plate in the abovementioned painting. This plate was originally painted with white and blue. However, the blue smalt has turned brownish-grey. For my thesis, I made a digital reconstruction of this detail:

Detail of The Well-stocked Kitchen.

Detail of The Well-stocked Kitchen, digital color reconstruction. (Source: Kirsten Derks)

This digital reconstruction serves as a visual aid to show the profound effect of the discoloration. Some discoloration in Beuckelaer’s paintings seems to have less impact than abovementioned example. Beuckelaer also used smalt in the modelling of his fabrics and garments. He used the blue pigment mostly in shadows. Because of the discoloration of smalt, these shadows have turned lighter in color and the modelling of the garments has flipped. This causes the garments to lose their three-dimensionality. Even though the discoloration might seem less serious at first glance, it does have big consequences: the garments painted by Beuckelaer now seem less convincing in their stofuitdrukking than they were when the paintings were freshly painted.

We know that Beuckelaer was actually very skillful in the depiction of different fabrics and textures (what we call stofuitdrukking). Karel van Mander writes for instance that Beuckelaer was hired by his contemporaries to paint garments and fabrics in their paintings. One of these contemporaries is Anthonis Mor, a famous portrait painter. The Rijksmuseum has two of his beautiful paintings in its collection.

Anthonis Mor, Portrait of Sir Thomas Gresham, ca. 1560-65. (Source: www.rijksmuseum.nl)

Anthonis Mor, Portrait of Anne Fernely, ca. 1560-65. (Source: www.rijksmuseum.nl)

The fact that an excellent painter, such as Anthonis Mor, hired Beuckelaer to paint garments, speaks to the fact that Beuckelaer was highly appreciated for his skills by his contemporaries. His stofuitdrukking is (partially) lost in his own paintings, unfortunately. Some detail in Beuckelaer’s paintings – painted with more stable materials – show what he was capable of. Not only did he revolutionize kitchen and market pieces, but his stofuitdrukking and aim to convincingly imitate the visible world made Beuckelaer an important forerunner of seventeenth century still life.

This blogpost is a summary of my master’s thesis, titled: “Blue cabbages and invisible onions: Discolouration in the oeuvre of Joachim Beuckelaer”. With this thesis, I graduated from the master’s program Technical Art History at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). The entire thesis can be accessed through the UvA thesis database.